The latest single from Birmingham wildcards Tall Stories offers an exquisite dose of paranoia and cynicism atop a jarring rumble of tenacious post-punk instrumentation. The Mic is proud to present a world premiere of Nosebleeds, alongside an exclusive and extensive interview with frontman Louis Griffin, who discusses the new track, the rise of post-punk, life in lockdown and more.

Over the course of eighteen months, Birmingham-based four-piece Tall Stories have traversed both the traditional challenges of kickstarting a new band alongside the unprecedented experience of navigating Britain in lockdown. Their first two singles were followed by support from BBC Introducing and the Midlands grassroots scene, sparking a fervent excitement for the band’s return this year, with a new release and a new band member in tow. Consisting of Louis Griffin (vocals, guitar), Francesca Hall (vocals, drums), Oliver Hill (bass) and latest addition James Marson (guitar), the quartet channel the ruthlessness of post-punk’s double-edged sword to great avail on their latest track Nosebleeds, demonstrating a remarkable maturity from a band that are seemingly only just getting started.

Whilst the band’s debut single, Lost in Translation, gathered local acclaim in a city yearning for a new indie champion after the demise of Peace, a breakneck summer in 2019 sparked an intense writing period, from which sophomore release Concrete Heads was born out of, kickstarting Tall Stories’ affiliation with heavier, politically charged tendencies. The band’s third single Nosebleeds however pushes them unabashedly into the post-punk dimension, slotting neatly between the likes of up-and-comers Talk Show and Do Nothing, of which the latter’s frontman Chris Bailey was a notable inspiration on the new offering, as frontman Louis Griffin notes. ‘I much prefer knottier and more interesting lyrics, somebody that comes to mind is Chris Bailey from Do Nothing, who is able to provide one couplet after another with so many references that it is almost an overload, and I wanted to do something like that.’

Inspired further by Protomartyr’s Joe Casey, the jubilant frontman states that he ‘was determined that [Nosebleeds] was going to be better lyrically, that this was going to have a lot more going on. Joe Casey and Chris Bailey really inspired this, people that you could spend a couple of hours with their lyrics and still be spotting little references afterwards. Something that Chris does brilliantly that I love is that he peppers in references that you would not expect in the songs, things from The Simpsons and It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, and The Truman Show…things that you don’t realise until you suddenly spot them on screen. It gives the songs a sense of longevity and that’s really important. I love that there are things afterwards that you don’t notice until months later, and there is a lot of that in Nosebleeds. There are really oblique references that make sense really to nobody else but me, but I really really like that.’

As a single, Nosebleeds is a snappy yet snarling monolith marking a leap forwards for the band, as they carve out their own niche within post-punk. A bludgeoning call to arms that resents the very fabric of reality that its creators have been forced to live under, the track lyrically presents a bleak narrative of the developing generation of actors and activists, presenting itself as a blistering indictment of the scene itself and the way music is consumed in the present day. Over the course of the track, Griffin delivers a monologue covering everything from Chekhov’s Gun to mutually assured destruction, all within the confines of three minutes. Despite the frontman’s rambling dialogue, there is nothing haphazard in the track’s objective to secure the band’s jaunty but swaggering sound for the future, a future that looks even brighter with the addition of new member James Marson on lead guitar, who immediately showcases his instrumental worth to the group in the guitar break towards the latter half of the new single. A back-and-forth lick between the guitarist and Griffin, reminiscent of The Jam’s News of the World, drifts in and out of sync, as Marson’s addition provides the band with room to breath sonically, in stark contrast to Griffin’s yearning for fast-paced and rolling wit in the lyrical dimension.

‘We’ve just put all of our energy into the release and into doing it justice…it feels like we’re getting closer and closer to the sound we’re after and the sound that’s in our heads.’ Louis Griffin

‘Going into Nosebleeds, we had two singles out,’ Griffin recalls. ‘We had Lost in Translation and Concrete Heads. Lost in Translation was our first single and although we might not be the biggest fans of that song now, as any band who has a song that people latch onto, when we play it live, people know what it is but I don’t think it sounds very much like us right now. With Lost in Translation, I think we were straddling the heavier end of indie, rather than moving into post-punk and I think that came with not really knowing what post-punk was and what the sound we were angling for was. I think we were reaching for post-punk but we didn’t know that post-punk was there to reach for. Lyrically, a lot of those lyrics were very descriptive, a lot like what Alex Turner was doing on the first Arctic Monkeys album, pointing at things and going look at this.’

'Then we had Concrete Heads,’ the frontman continues to explain, ‘which is actually a very simple song, and we were listening to a lot of post-punk at the time, specifically IDLES, and that song had two functions. One is quite a simple one in that we needed something to open our shows with, and I had this image in my head. IDLES start with Colossus usually in their sets, just a very simple bass note and a drum beat. Concrete Heads starts with one bass note and a drum beat…and I really like that, it’s a very simple way of starting a gig and getting people to pay attention because you can control the way that it builds and people react to that really well. On the other hand, I wanted to write something that reflected more of what I wanted to write about. I think a big part of Tall Stories’ DNA, and it wouldn’t have been obvious if you listened only to Lost in Translation, is that there is a lot of politics in there, there is a lot of all of the post-punk things in reacting to different bits of culture and that. With Concrete Heads, it is essentially a protest song about how much it feels that there is no way of getting through to the establishment. Coming out of it, although I liked how it was punchy and bare-bones in quite an economic way, I felt it was too far that way. The lyrics for example…there are barely any lyrics in there. It is very trim, and it was great for what I needed it to do at the time but that was not quite my writing style.’

Whilst Griffin confirms that the arrival of Nosebleeds projects his ambition for a lyrically-expansive and vehement sound, a vital catalyst behind the band’s current evolution rests on the addition of James (Jim) Marson on lead guitar, a move which the frontman notes was made purely from a performative point of view. ‘As a three-piece, I couldn’t put down the guitar and I feel like a lot of the frontmen and frontwomen that I look up to, especially in post-punk where it is quite uncommon for them to have a guitar in hand, I love the directness of the performance, and there is an element of heightened theatrics within the performance and the genre. It is essential to have the frontman freed up for at least some of the performance. So we recruited Jim on guitar as our fourth member, who is an insanely talented guy and makes me look vaguely competent.’

‘I think with the space to think and the clarity that lockdown has provided, we’ve been able to focus on our aims and what we want with our sound.’

The frontman recalls how the recruitment of Marson took place in December 2019 when the band convened for the holidays. ‘It was becoming clear that although we had these songs we were really proud of, performance wise, Fran kept on talking about how we were going to solve this problem because we were getting really good reception, particularly after the gig we did just before Christmas,’ Griffin sighs. ‘It was the best gig we played…the crowd were so invested in what we were doing but we just kept saying that we needed to be doing more. There is this directness that you get with a frontman with just a mic. I’m reminded of seeing Spector play and there was this laser-focus between the crowd and the performer, and that was the step that we were missing…that was the bit that we were reaching for. We had to figure out how we were going to do this. We talked about potentially doing songs with just bass and that was quickly thrown out, so we knew really that we needed another guitarist.’

Marson, a long-term friend of bassist Oliver Hill had been on the band’s radar for over a year before he was approached to join the band, Griffin recollects. ‘We actually met for the very first time at our local pub on Christmas Eve before my nineteenth birthday last year. He was top of the list of people we wanted to ask, and so we got him along to the pub. Jim is the most personable, nicest guy. He’s also like me in that he can’t sit still. He’s a really competent guitarist and I think he hadn’t been involved in the post-punk end of things before he came to us. He was into The Jam, The Clash and those kind of bands, but he completely gets it and is just as invested in the vision as all of us. Our first gig together as a four-piece was at Mama Roux’s in Birmingham in February and it felt very organic and natural.’

‘One thing that is very interesting to me, specifically in this country, is that lockdown has provided a really crystal clear message that this government, the people that are in power in this country, not only do they not care about you and I, they are happy to let us die.’

Despite the newfound importance for acquiring a fourth pillar in the rising Birmingham institution, Griffin projects an almost nervous animosity surrounding the recruitment of the much-needed new member. ‘This was not a decision we took lightly,’ he quivers. ‘We really prised our dynamic within the band. We are first and foremost mates, and also with that comes a certain level of trust that builds up after a while in the songwriting process. Adding a new member into that almost sets you back in that you have to regain those [bonds]…it’s almost in the ability of being able to just say an idea within the safe space of the band and not worry about it being crap or being judged. It’s just about getting honest feedback, and that can be harder to do with a new person.’ Over lockdown, Marson launched his own clothing brand [The Black Country Archive] which for Griffin showed that ‘he would be really invested in what we were doing. I knew that he was going to be here for the long run and so he joined and that just gave us room to breathe. He could be holding it down on guitar and I wouldn’t have to do anything. Equally, I could write him guitar bits that I couldn’t do when I was performing, and I could forget about it and he could handle that. The main thing with Jim was that he gave us room to breathe, he gave us extra space to do interesting things.’

Whilst the frontman explains that ‘Jim was very clear when he joined that he wanted to help us execute the vision we had and was there to facilitate that and help us’, the addition of a fourth member has injected further creativity within the band’s melting pot of influences, with Hill and Marson borrowing from Joy Division and The Jam respectively on the band’s latest release. ‘Me and Fran are very much from the same school of post-punk, following its bible, and Ollie is very much Britpop and Shoegaze, bringing another perspective, and Jim does the same as well,’ confirms Griffin. ‘Sometimes, when all your influences are within the post-punk sphere, and all you do and all you write about, this is about me now, you get too repetitive and you sink deeper in this rabbit hole and it’s really nice to have someone else presenting a different look at things. Especially when you’re getting a bit of a creative block, you can look over your shoulder and find a new way of doing things. It’s always been a nice thing to have different angles from different people in the band.’

Five years ago, post-punk as a genre would gather as much mainstream interest and attention as a newly released Peter Andre track. Yet the newly established four-piece emerge resolutely in an environment that not only welcomes post-punk bands, but actively encourages them to be bolder and braver than ever before. The likes of IDLES, Shame, Fontaines D.C. and The Murder Capital have sparked a new era for guitar music in Britain and Ireland and Griffin is quick to lavish praise on those that have risen in recent years. ‘We are indebted to these post-punk bands, first and foremost,’ he confirms. ‘We wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for these bands, we definitely wouldn’t be playing the same sort of indie, and thank God because I would not have wanted to play another song with four chords and Alex Turner lyrics. As lovely as that is, it died a death, and the interesting thing is, is that we came about in a scene that was dying a death.’

‘When we started out in Birmingham, there were no big bands,’ he continues. ‘Peace had already gone, nobody had heard from Swim Deep in years. Jaws…it’s really depressing because we met at a Jaws gig and I still think they’re quite a good indie band…they all have day jobs, and that was so discouraging as a new band coming up. We came about as one scene was declining and another was starting to come up, so we’re sort of indebted to that.’ When asked if the current musical landscape has helped his band develop, he smiles and nods, explaining ‘I think a lot of people would say, and with fair reason, that we’re just part of the rise of post-punk, hanging onto the coattails of other bands. The genre is obviously having its moment in the sun.'

'We have these bands, the specific one that comes to mind is IDLES, who about five years ago would have come across as an incredibly uncommercial option, but now are selling out Alexandra Palace in a day. This is not underground anymore. Obviously that comes with pros and cons because now there’s interest. The top of the industry is starting to realise it, which pulls up everything else as well. All the small labels, all the magazines take an interest now, so it’s easier to get up there but at the same time there is more. To stand out from that crowd is increasingly difficult. It is also increasingly difficult because you then feel like if you’re not doing the most interesting and the most avant-garde thing, then there’s not that much worth to what you’re doing. That was something that we really struggled with between Concrete Heads and Nosebleeds. There’s quite a big gap between those songs…for us, post-punk was the most incredible, the most exciting thing in music…to then feel like “do we have a place in that, are we on this level with these guys?” Obviously your brain’s going no, don’t be stupid, but then overcoming that, and trying to do it anyway and get near that…that’s the thing that any band tries to wrestle with.’

‘In terms of my mental health, I think a lot of people, me included, are confronting mental health for the first time…actually asking for support myself was something I’d never had to do before.’

Griffin speaks with an eloquence and a clear understanding and admiration for the genre he is attempting to navigate, yet he is aware of both the potential pitfalls that await new bands reaching for attention as well as the inherent issues that unintentionally reside within the monolith of post-punk as a movement. ‘With the over saturation of the genre, and this is something that gets mentioned a little bit in Nosebleeds, you get that element of self-congratulation, an element of everyone is looking at one another and thinking this is amazing, we’re all amazing, it’s all fantastic, and I have two criticisms of that. The first one, and I think this is something that the whole genre wrestles with, is that post-punk is inherently political and disruptive. It wants to upset the status quo. At the same time, it doesn’t upset the status quo…much. It does have an effect on certain things, for example watching bands interact in the Black Lives Matter movement for example, but it is not flipping the table of our culture, and that’s something to wrestle with.’

‘Also, there is this element of everyone patting each other on the back, and I think this is something that Sports Team have cracked the surface of,’ Griffin offers. ‘Everyone is very nice to everyone these days, and it’s because it is so hard to be in a band now. It is hard to make any kind of living in a band. We have made no money in the band, and that is not surprising, we wouldn’t expect to, but bands ten times our size have still not been able to make a living in a band. There’s not even people at the top making a good living out of it, and because of that, no one wants to knock anyone else down. Everyone is always saying how amazing everyone else is, and I like that, I like that we have gotten away from the macho Britpop pissing contests, but equally it has now become very safe and there’s not an edge to it. When Sports Team started to shit talk on bands like HMLTD and that, everyone kind of went “oh you can’t do that!” and they got headlines out of it. I don’t know which is better. I don’t know whether it’s better or whether it’s healthy for everyone to be congratulating everyone else.’

The frontman highlights how Nosebleeds attempts to address this developing phenomenon within the industry, with the track ‘acting as a symbol for radiation poisoning and the knowledge that something is wrong…here’s a very visible sign of that…but we can’t quite figure out what. I liked that barometer of where we are at and the genre is at.’ He firmly states however that ‘obviously I have to preface everything I say about post-punk by saying that I’m a huge fan, this music has given me so much, and especially bands like IDLES, who have really changed me as a person and the way I look at thing…everything they’ve done around masculinity and things like that, there’s so much that I’m indebted to and I hate throwing any stones at it because this thing is really great and beautiful and I do love it all.’

‘I don’t think a lot of people, students especially, are aware that when their cities return to normal, there aren’t going to be venues for nightlife to be in.’

The four-piece’s commitment to following in the footsteps of the genre’s stalwarts has allowed the band to hone in on the sound they have respected for so long. ‘The demos that we’ve been doing recently for our future work, they’ve been unabashedly post-punk in comparison to what we’ve done before,’ confirms Griffin. ‘Up until now, we’ve not been able to fully commit to the sound, because of what most artists have, in that self-doubt that we can’t quite pull off what we want, and then because of this single and feeling like we’ve gotten quite close to that sound we’re after, we believe that we can actually get to that place. Post-punk is a very particular thing. By nature of it being post-punk, it is defined as being a reaction to this very specific sound, so there’s always this feeling that you have to be doing quite cerebral things. What lockdown has made us realise, is that we can actually do those things and we were capable of that anyway. We just had to believe in ourselves that we could write that sort of thing. There’s been a definite evolution of our sound over lockdown.’

Griffin additionally proclaims that over the course of Nosebleeds’ development, ‘there’s been a definite shift in what we thought and feel we could reach for. There’s been a focusing of our sound.’ He adds that ‘before lockdown had started, we were still mixing the single and sending the mix back-and-forth [which] was quite annoying actually because usually you’d just sit in a room and get it done but we couldn’t do that so there was a lot of sending files. I think with the space to think and the clarity that lockdown has provided, we’ve been able to focus on our aims and what we want with our sound.’

2020 acts as a stark contrast to its predecessor, a year in which the band started to make a name for themselves in the burgeoning local scene, supporting local indie royalty Swim Deep at one of their three comeback shows at The Sunflower Lounge in Birmingham, whilst winning Truck Festival’s competition to open the So Young Market Stage in the summer. The lockdown climate that begun in March 2020 however, created a seismic shift, as the band were forced to adjust to a new world, one which provided space and time to focus. ‘I think up until now we’ve all been really very busy people, spinning a lot of plates at once…firing on all cylinders… and the band has sometimes had to play second fiddle to a lot of things and it’s usually been down to being in town together over a weekend that we’ve been able to do some writing. It was a lot of sporadic bursts before lockdown.’

‘What lockdown did,’ Griffin continues, ‘was that it removed all my obligations university-wise, and I just had space to breathe, and so I did that for a couple of days. It wasn’t a conscious decision to be productive in lockdown in terms of consuming and creating. It came down to something within me already, that inability to sit down and do nothing for five days straight, I reach a wall very quickly where I need to be doing things, whether that’s going out for a run or reading and watching things. Lockdown has been a time to be able to completely focus on my creative stuff. I decided I wanted to use this time for good, and we were very lucky to get some funding through an EU-funded scheme, so I bought myself basically an entire home-recording setup. I bought a mic, an adapter, audio software…the works, and so what I’ve been doing in lockdown is demoing and the others basically have a similar setup so what I do is have an idea, and whereas usually we would then go to a practice room and play it and jam around it and eventually end up with something, I’m now doing that but recording it, sending it over to everyone, and they’d send it back with some additions and that happens virtually. I guess to an extent we’ve been used to the distance as a band, but lockdown has changed the way in which we work.’

‘Whenever I look at a music video for example, it affects my perception of the song. Cover art as well, I’m not afraid to say but if different albums had different cover art then it would probably quite drastically affect what I think of them, and that’s weird to confront that.’

With his own isolation setup installed, the integral frontman has regained his tenacity to be firing on all cylinders once more, using music to numb the shock of lockdown Britain. ‘It’s been lovely to be honest, especially band-wise,’ Griffin exudes. ‘I’ve got more ideas than I could ever work on. I’m hopeless, if there’s an instrument in the room, I can’t sit and look at it without picking it up, and I’ll often play around with it and record a five-second thing that I like and then return to it later when I’m in a writing period and I’ll see what’s actually good in the light of day. My voice notes app has been full in lockdown, and that’s how I like it. It’s been a very creative and monastic existence.’ The singer keenly notes the effect that lockdown has had on his band’s new release specifically, stating that ‘we have always been quite bad at doing things speedily. I think it comes from being in different cities with uni and whatever and lockdown let us focus on it and get it sorted. We had a lot of delays that were out of our control…but once that was done, everything started moving really quickly. It’s just so good to get that feeling of achievement from it all because usually that’s what we’d get from gigs but we can’t do that. We can’t promote it in the way we’re used to and want to so we’ve just put all of our energy into the release and into doing it justice…it feels like we’re getting closer and closer to the sound we’re after and the sound that’s in our heads.

Yet despite his rejuvenated optimism towards Tall Stories’ current output, Griffin offers a sincere and frank discussion surrounding life in lockdown, vehemently lambasting how Britain continues to act in comparison to her global counterparts. ‘Lockdown has been a very strange thing to live through,’ Griffin sighs. ‘It has been something that people are going to look back on, our kids are going to ask us about it. This is not something that I am the only one to notice. One thing that is very interesting to me, specifically in this country, is that lockdown has provided a really crystal clear message that this government, the people that are in power in this country, not only do they not care about you and I, they are happy to let us die. That is the baseline, they were happy to do that,’ sighs of exasperation trail each sentence. ‘What baffles me is, I’ve got a lot of friends in other countries who are way past lockdown, and talking to one of them in Australia, talking about all of this, she was saying how she didn’t understand why we weren’t looking at the death tolls and overturning the government. They’ve killed people! We are the worst in Europe and the worst for our size in the world but over here, no one really realises this. It’s that weird feeling that if we all just closed our eyes and went down to the pub, none of this really happened. It is that realisation that no, that is not ok, people died, this hasn’t stopped happening just because someone on television has said it’s stopped happening.’

As clouds of anguish draw over the young aficionado, he expands on his harrowing assessment of modern Britain. ‘It really reminds me of my favourite documentary called HyperNormalisation by Adam Curtis. To me, it’s the perfect example of why I love the BBC and all those cultural institutions in this country, because I don’t think anywhere else would have made a three and a half hour documentary about very abstract societal concepts.’ Griffin continues to explain that ‘hypernormalisation was this concept in Soviet Russia where people are sat at home and going to the shops, and there’s no food. Nothing is happening. It is quite obvious that everything is collapsing around them, but you turn on the television and the Minister for Food is saying that productivity is up six hundred percent, and all these stats saying that everything was great. And people would believe it…they would buy into it and actually believe that that was happening because the alternative was to realise that their entire worldview was completely false. I don’t think we’re at that level yet, but I really think we’re somewhere along that scale. If The Times and Boris Johnson and the nice man on the television say that if you wear a mask in a shop everything is going to be fine, it’ll be fine..and it’s not going to be fine, but if we all believe that then we don’t care, as we’re herded off. So that’s what’s happening, and that’s where the base level of where my head’s at at the moment.’

'We wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for [post-punk] bands, we definitely wouldn’t be playing the same sort of indie, and thank God because I would not have wanted to play another song with four chords and Alex Turner lyrics.'

The clarity of Griffin’s current sentiments has seemingly percolated into the four-piece’s creative mindset, with the world’s dismal array of affairs providing apt inspiration for new, socially rapt material. ’In terms of what lockdown has done to us as a band…the stuff we’ve been writing, the demos have been some of the most politically charged stuff we’ve written,’ the singer nods. ‘Concrete Heads is probably the most overtly political of our three songs, but it’s also quite oblique in how we talk about it. It acts as a metaphor for those people not listening and not caring. The new stuff…it’s not metaphors,’ a wry smirk cascades across the frontman’s face. ‘It is really, really angry. It wasn’t a conscious decision…we were writing around the week after George Floyd’s death and the message we had was not subtle at all…it’s become much more angry.’

The anguish entwined with Griffin’s voice fails to subside as he bemoans a fractured society that looks more on the verge of collapse than repair. ‘One thing that I’d written before this,’ he recalls, ‘I had an idea for what was wrong with society and I don’t know now how it will hold up after lockdown, whether people will just be like “yeah, we know that now dickhead”, it was this news story that I had read just after Christmas last year. A homeless woman had given birth to twins on Christmas Eve outside Kings College in Cambridge, and nobody had stopped to help her. Someone eventually called an ambulance but it was about three hours after she had given birth, and I read this story and was like “that is what’s wrong with this country.” I couldn’t have written a better metaphor, and it really depresses me that I didn’t have to write a metaphor. You’ve got this institution with billions of pounds, and this woman with absolutely nothing, and there is no connection between the two. It’s like a different planet. People were walking past and it’s Christmas Eve in Cambridge, and it’s all lovely, and I guarantee people probably saw what was happening and crossed the street to avoid it. A lot of the new demos are super political.

Whilst lockdown Britain has sparked a vitriolic approach to the band’s creative process, Griffin additionally delivers poignant hues of reflection on his own state of mind throughout the past four months. ‘Mentally, lockdown has not been good for me,’ he certifies. ‘In terms of my mental health, I think a lot of people, me included, are confronting mental health for the first time. I have a lot of friends who have mental health issues, and I’ve been very well acquainted with supporting them but actually asking for support myself was something I’d never had to do before. I’m a very social person so spending a lot of time on my own wasn’t good for me. I think that’s why I’ve been so creative in lockdown, because if I do nothing, I can’t not think about what’s happening in the world. In the band, it’s brought us closer together really. Honesty, just saying how things are, how we’re feeling, has become really crucial…and with the demos, dropping all pretences at the door and asking for honest feedback. I need to know if something is shit, I really like that, because there is no barrier between any of us on that level. Equally, when we achieve something, there’s that real gratification because we know that we’re all on the same page with that. Lockdown has brought us closer together but we’re now facing a horrible landscape. Lockdown has affected the industry, I have no idea what we’re going to be coming out of this into and we’re going to have to reevaluate things when that happens, but it’s going to be a very different world I think.’

‘With our sound and our setup, and post-punk being a fairly DIY genre, what we’re craving more than anything is to just get in a room and play really loud music because so much of our sound comes from that natural back-and-forth and that is hard to replicate digitally.’

His musings on the post-lockdown climate cause industry worries to spring into conversation. The news of prestigious Manchester music venues Gorilla and Deaf Institute closing and subsequently being saved to the surprise of many highlights a volatility that the grassroots industry has not experienced to such a great extent. ‘This is the opening shot in a battle that is going to rage on for quite a while,’ Griffin declares. ‘I don’t think a lot of people, students especially, are aware that when their cities return to normal, there aren’t going to be venues for nightlife to be in. It’s going to be the months after lockdown where these venues are going to be trying to recoup all those losses and stay open that are going to be critical. Even after lockdown finishes, the losses are still going to be carrying on. I’m encouraged by the community itself. Within the industry, people are obviously shocked, and it reminds me of when people banded together to save Loud and Quiet magazine and [music venue] The Windmill. We know how important [small venues] are to bands bigger and smaller than us, everything in between…it’s an essential ladder to greater things that people outside of the industry don’t quite grasp the importance of. If those things aren’t there, you’re just not going to get bands. It’s really simple at its core. The answer is also really simple. They just need money. It spins my head that the people in charge just can’t see that, and also can’t see how necessary all of this is.’

A hint of optimism creeps into Griffin’s dialogue as he suggests ‘it is encouraging that people are banding together to save them. I just wish that the support was coming from something more centralised. The problem with fundraisers and donations is that they are not regular, consistent support, they are a one-time thing. The change we need is structural and systemic, and that can only come from top-down, from the government down to the industry or from the industry-leaders down to the grassroots. Neither of those groups of people want to do anything about the problem, because to do something about the problem would be to directly disadvantage themselves.’ This dichotomy is alarming for Griffin, who explains that whilst the band have adapted to recording in the lockdown environment, ‘with our sound and our setup, and post-punk being a fairly DIY genre, what we’re craving more than anything is to just get in a room and play really loud music because so much of our sound comes from that natural back-and-forth and that is hard to replicate digitally.’

'We really prised our dynamic within the band. We are first and foremost mates, and also with that comes a certain level of trust that builds up after a while in the songwriting process. Adding a new member into that almost sets you back in that you have to regain those [bonds]…'

As one piece in a wave of new bands attempting to find a place within an industry that teeters precariously on the edge of breaking point, Griffin confirms that lockdown has shifted Tall Stories’ priorities towards a more creative atmosphere. The release of Nosebleeds marks the beginning of a new era from an aesthetic perspective, as Griffin and co. scrutinised the visual experience that frames the music. ‘For a lot of bands, the music is the most important thing,’ Griffin says. ‘For me, and a lot of the bands I love, everything around the music, like the graphics and the way you experience the music, are really crucial. Whenever I look at a music video for example, it affects my perception of the song. Cover art as well, I’m not afraid to say but if different albums had different cover art then it would probably quite drastically affect what I think of them, and that’s weird to confront that. For me, the art direction is nearly as important as the music itself, so I’ve got to put my money where my mouth is.’

In order to stay true to his quest of creating a visual experience that intertwines perfectly with the music, Griffin explains that ‘about a year ago I taught myself how to use Photoshop, very rudimentary, not claiming to be a designer at all. That for me however was really crucial because I’m obviously in charge of the lyrics and the interplay of that with the visual identity of the music is really important, and almost to do the music justice you’ve got to have that other thing as well nailed, the way that people experience it. With Nosebleeds, I was determined from the very start that it was going to have a completely clear visual language. We were going to undergo a rebranding, which we did for Concrete Heads as well, so we’ve had new press pictures. Concrete Heads was brutalism…it was concrete and depressing and urban. Although other people find it depressing, I actually love brutalist architecture. Nosebleeds in comparison is leafy, it’s naturalistic, we’ve changed our fonts from these brutalist, post-Bauhaus fonts to these Serif, traditional, more-tangible fonts.’

‘Concrete Heads is probably the most overtly political of our three songs, but it’s also quite oblique in how we talk about it. It acts as a metaphor for those people not listening and not caring. The new stuff…it’s not metaphors…it is really, really angry.’

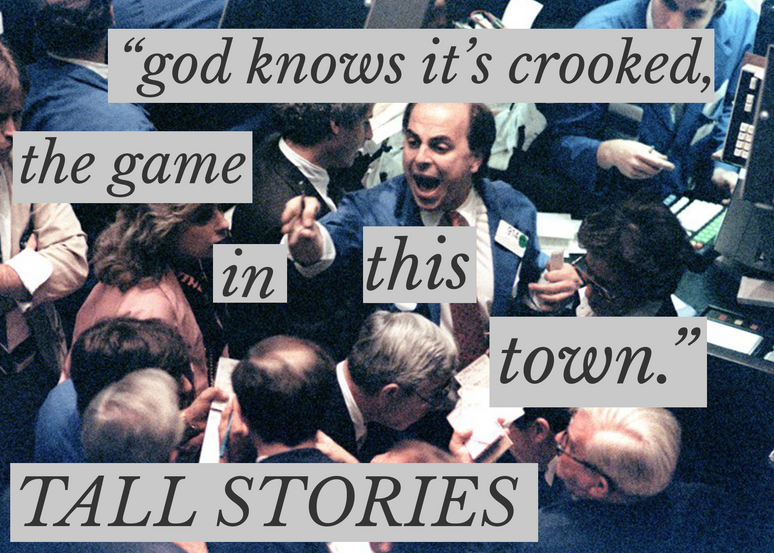

Griffin confirms that the band’s promotional campaign for Nosebleeds hones in on the fabric of the post-punk movement. ‘For me, [the campaign] arcs back to post-punk’s history with DIY-ness and collage, which is really important to punk and post-punk, where a lot of flyers and the album art would be made by the band. They’d cut out letters and create these artworks. For the promotion of Nosebleeds, I selected three lyrics that I really liked as standalone statements from the single, and we made three separate graphics that were like those collages but were updated and were done digitally with old stock images from the 50s and 60s. There was a nuclear blast, a nuclear family and there was a photo from right before the first Wall Street crash. Those things felt just as much a part of the single as the music itself, it was like an extension of that, and that is really important to me. I spent hours deliberating over that myself.’

‘Then there’s the album artwork’ Griffin continues, ‘which we had much bigger things planned but lockdown hindered that, which was going to be a big narrative music video, and we hope to still do that at some point, and the front cover is just a window into what they would have been. It is actually Fran’s sister on the cover because obviously we had to do if from lockdown. Fran got some fake blood and a really important thing for me was the tactileness of the image. She only took it on her phone, which makes it seem grainy, tactile…feels real and older, the cover art was influenced by the likes of Visions of a Life by Wolf Alice and the three single artworks from that. Baxter Dury’s latest campaign also inspired this, it featured some fantastic film photography from Tom Beard. I have a lot of respect for bands that have their own visual languages, so we’ve done a cover as it would be in real life.’

The frontman additionally notes that a lockdown video will accompany the release of Nosebleeds, but in an unconventional format that Griffin hopes will appear endearing. ‘We were planning on doing a socially distanced video, and my inspiration for this comes directly from certain videos I’ve seen from Talk Show and Fontaines D.C. as they included landscape and they were out and about and it felt like they were making something specific, rather than just because it was lockdown. I was worrying about how we were going to do the sound as we didn’t have really expensive sound equipment, so I though why don’t we play up to that, as a big part of our lockdown input was that we have had these restrictions and either we strive for something that’s not quite possible and ok we might not get there but the flaws are going to be obvious, or the flaws are going to be obvious and we embrace them, which is something I call the Sports Team approach. The video is filmed in a field and a forest. It’s us playing our instruments, but it’s obvious that we’re not actually playing them, you’re hearing the single in its recorded form and we play up to that. Jim is quite obviously playing the wrong chords, I’m holding a mic that’s blatantly not connected to anything. Fran is drumming without any cymbals, she’s sat on a tree stump doing that, and it’s fine…it works. The DIY-ness is the video, it is part-and-parcel of it. It’s a compromise I guess, under the circumstances it is the best that we’re going to get.’

‘When Sports Team started to shit talk on bands like HMLTD and that, everyone kind of went “oh you can’t do that!” and they got headlines out of it. I don’t know which is better. I don’t know whether it’s better or whether it’s healthy for everyone to be congratulating everyone else.’

The unique experience of creating art in 2020 has forced the band to take an extreme yet impressive step in the making of their first visual release with Nosebleeds. ‘We were thinking about how to navigate this during lockdown,’ Griffin projects. ‘We don’t have the money to do a vinyl run at the moment. We ran through multiple options, like USB’s and CD’s, but we were at a bit of loss because no one buys CD’s anymore. Then we just thought we’d embrace the restrictions like we did before. So we are doing CD’s, but we’re making them an object. It’s not really about the CD’s, it’s about the object. We’ve got these cardboard sleeves and we’re going to sit down and make physical versions of the collages we posted before for Nosebleeds, not just those three lyrics…it’ll be ten CD’s with ten different lyrics and ten different collages based off of those lyrics. They are going to be very, very limited and that’s the beauty of it. It’s an object, something to be displayed and held, and hopefully we’ll do it justice on that count.’

The arrival of Nosebleeds ushers in a new era for Louis Griffin and Tall Stories. The track’s uncompromising stance provides amble evidence that a new outfit is in town. 2020 has shaped the band to such an extent that it would be naive to expect their dynamic future to be anything short of exceptional. The turmoil of lockdown has harnessed a surge of anger and creativity within the four-piece, who are veering towards a path more unpredictable and dangerous than they could have predicted at the start of the year. Yet with a new member in tow alongside a sharper, more-refined sound in play, an uncompromising creative vision and workaholic tenacity, Tall Stories are on track to make clear-cut incisions into a genre and industry that continues to embrace the brave and the broken alike.

Nosebleeds is released on all platforms at midnight. Readers can hear the release exclusively here now.

Comments